Three ways to focus landscape photos

Maximise your DoF

When photographing a landscape we usually need to maximise the DoF to ensure that the entire frame is in sharp focus. Landscape photos are most commonly made with a wide angle lens; between 14 and 35mm are popular choices.

Selecting a smaller f-stop, between f/8 and f/11, will give you good DoF as a starting point. Stopping the aperture down past f/16 will cause a progressive loss of sharpness due to diffraction.

If you can't quite gain the depth of field that you need, it's often better to move the camera back a bit than to stop the lens down further. Even moving backwards by as little as 0.5m may give you the DoF you need without stopping down past f/16.

If there is nothing in the immediate foreground then no problem, just focus at infinity and fire away.

When you have a situation where you want to include an object in the foreground, let's say a nice rock, and you want to keep the background sharp you'll need to employ a different focus method.

Here are three to try:

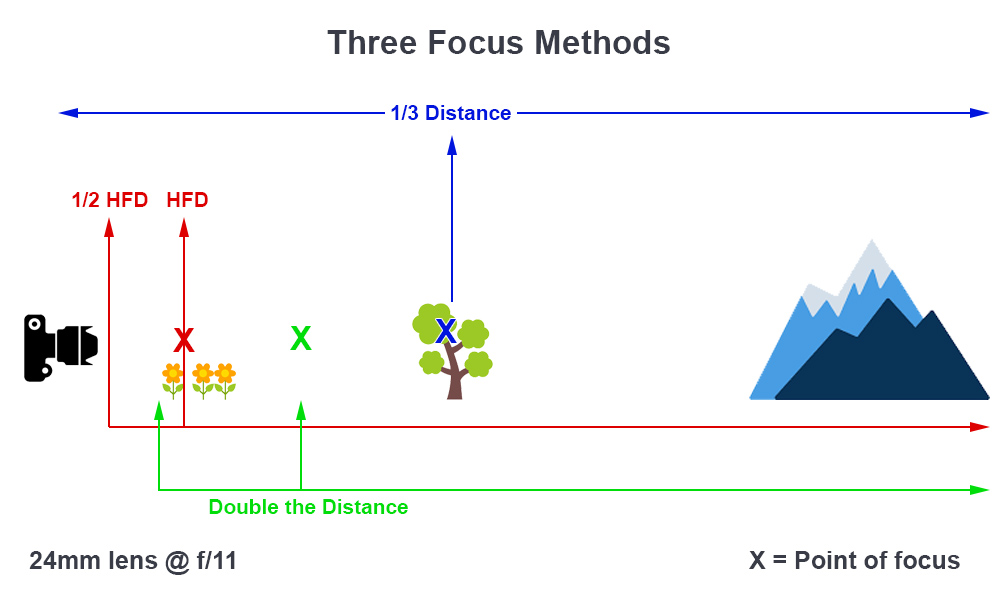

1/3 Focusing

Study the scene through your view finder and find a point that is around 1/3 of the way into the frame. Focus on this point.

This simple focusing method works because the DoF will extend from about 1/3 of the distance toward you and 2/3 of the distance behind the plane of focus. With a wide lens and a small aperture the depth of field should cover just about all of the frame.

If nothing in the frame is particularly close to the camera this method will work fine.

Hyperfocal distance focusing

The most accurate way to focus and achieve maximum DoF is to use the hyperfocal method. By definition the hyperfocal distance is the closest focusing distance at which objects at infinity will be acceptably sharp. In other words, the foreground and the background of the image will have equal sharpness.

Once you have calculated the hyperfocal distance you can be confident that everything in the frame from half of the hyperfocal distance to infinity will be in focus.

For example, if the hyperfocal distance is 3m then everything from 1.5m (half the hyperfocal distance, measured from the film plane) to the distant horizon will be acceptably sharp.

Unless you are an absolute genius at mental arithmetic, calculating the distance in the field will require an app or at least a chart:

HFD = f2 ÷ (Nc) + f

f = focal length

N = f-stop

c = circle of confusion limit

Fortunately there are plenty of apps available to calculate HFD. You will need to input your camera sensor size, lens focal length, and f-stop, the app will give you the hyperfocal distance.

Here are a few common examples (assuming a 35mm camera):

16mm lens @ f/8: HFD = 1.08m

16mm lens @ f/16: HFD = 0.55m

24mm lens @ f/8: HFD = 2.42m

24mm lens @ f/16: HFD = 1.22m

28mm lens @ f/8: HFD = 3.29m

28mm lens @ f/16: HFD = 1.66m

I'll bet these distances are less than you would have expected.

Remember, focus on the hyperfocal distance, any object that is within 1/2 the HFD and the horizon will be in focus. Just make sure that nothing appears in the frame that is closer than that distance.

The method I mentioned earlier, focusing on a point 1/3 of the way into the frame, is a kind of quick and dirty version but will give acceptable results most of the time. HFD focusing is not easy or quick but is accurate.

Double-the-Distance focusing

This method of focusing might be the best and most practical to use in the field. It uses the principles of hyperfocal distance focusing but in a much more user friendly way.

Let's say you wanted to make a photo with a mountain in the distance and an interesting rock that is in the foreground and quite close to the camera. Ideally, you need the rock and the mountain to both be sharp.

As we now know, anything from 1/2 the HFD to infinity will be in focus.

All you need to do is estimate the distance to the rock and then double that distance. If the rock is 2m from the camera simply focus on a spot 4m away and, boom, front to back sharpness.

You could carry a tape measure around with you (not ideal), or step out the distance, or just learn to estimate the distance with a reasonable amount of accuracy. The way I do it is pretty simple... If practical, I'll take the camera back until I'm twice as far away from the rock as I will be when I've set up my tripod. Then I'll just focus on the rock. Easy.

Another option is to invest in a large format camera with shift and tilt movements to change the plane of focus :)

Three focus methods

In the above image example, we would like to have the closest flower in focus and keep the mountain in the background sharp.

As you can see, in this scenario, any of the three focus methods would work as both the flowers and the mountain are within the depth of field.

It was quite convenient that there happened to be a tree exactly 1/3 of the way into the frame on which to focus. In reality it can be quite difficult to estimate 1/3 frame depth.

The closest flower is well beyond half of the hyperfocal distance so using the HFD method would obviously work well.

Using the double-the-distance method will always work as you are calculating the focus point based on the distance of the closest object. This method is as accurate as your ability to measure the distance. Another benefit of double-the-distance is that it will work with any unit of measurement including feet, metres, steps, or that long stick over there.

Focusing landscapes

And here is the final image. Isn't it beautiful, and sharp?

Double the distance focusing

The above photo is an example of double-the-distance focusing.

I wanted the bench seat and the city skyline to be sharp. The bench was about 1.5 paces from my camera. I simply moved the camera about 1.5 paces further back (plus a little bit), focused on the bench, then re-positioned the camera and took the shot.

Subscribe